How GMOs Are Conquering the World

Antoine de Ravignan - Alternatives Internationales

Rejected by a majority of European citizens, transgenic crops have taken root only marginally in the Old Continent: 108,000 hectares in 2008 in seven EU countries, three-quarters of them in Spain. But they've made their way elsewhere.

Protesters decry a Mexican biosecurity law that fails to prevent contamination of corn crops by GMO, an occurrence documented even for corn in its indigenous cradle. Yet, Mexico is one of the large countries polled where a majority favor GMO crops. (Photo: Marco Ugarte / AP / PA)

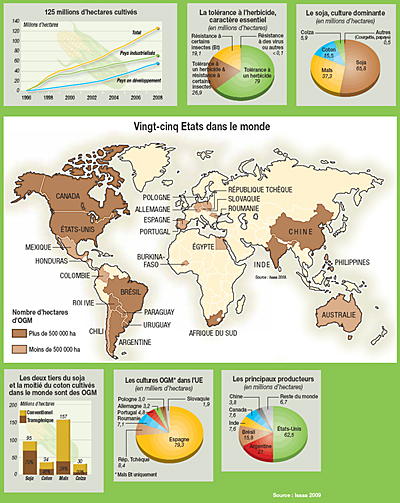

Last year, transgenic crops occupied 125 millions hectares in 25 countries, representing close to 8 percent of the planet's cultivated surface. And although the United States, Argentine and Brazil are far ahead in GMO cultivation, it is advancing rapidly in Asia and Africa.

Today, in practical terms, genetically modified organisms (GMO) amount to three crops: soy, corn and cotton. But those crops play a key role in the economy and, above all, in the planet's food supply. Forty percent of the surface devoted to commodity crops (grains, oleaginous crops) is intended for animal feed stock. And the soy-corn pairing, which predominates in animal feed, is largely transgenic today: 70 percent of global soy production.

Also see below:

Study Released in Argentina Puts Glyphosate Under Fire •

Why have GMO tended to become the global norm for crops ... except in the EU? The weight of public opinion has been decisive. A rare international poll, conducted in 2002 by a Canadian institute in 34 countries on five continents (1) demonstrates levels of acceptance below 42 percent in European countries (but also in Japan and Russia) and above 65 percent in the United States, China and India. Other big countries, such as Brazil, Canada, the Philippines and Mexico, seem to be favorable in the majority to GMO. Between the United States (50 percent of the GMO grown in the world) and the EU (0.1 percent), polls continue to confirm this huge gap in opinion, a reflection, among other things, of different attitudes concerning innovation and risk, eating and the values that are or are not attached to it.

Mobilization and Organizational Expertise

However, the European exception cannot be explained solely by the reticence of public opinion which, incidentally, may be quite favorable in some places (Spain, Portugal, Ireland, Bulgaria and Malta). Faced with seed company lobbying, anti-GMO organizations' lobbying has been effective and pushed decision makers to adopt legislation far more restrictive than outside the EU. Organized, endowed with genuine expertise, present in the media, perceived as legitimate by a great part of the population, these associations have weighed heavily in the public debate, calling on elected officials and mobilizing voters on the subject. In the end, there's hardly anywhere but the EU where all these ingredients - public opinion that is overall quite reticent, powerful associations and quite democratic institutions - are found together and combine their efforts.

National Moratoria

The result? A single variety, Monsanto's transgenic corn Mon810, is currently authorized for cultivation in the EU (2), whereas elsewhere farmers have an embarrassment of choice. That's the result of a complex authorization procedure through which, ultimately, in the absence of a qualified majority of divided EU member states, the files are systematically blocked, unless the Commission takes it upon itself to decide, which it did in the case of Mon810. But although the Commission may authorize, it cannot really impose: Since 2005, six countries, Austria, Hungary, Greece, joined by France, Luxembourg and, most recently, Germany (April 14) have unilaterally pronounced moratoria on that crop, which Brussels has had to swallow since it has been unable to obtain a condemnation of the violators from the other member states. And even in the countries where the corn is authorized, the prudential rules of the 2001 directive, adopted thanks to the anti-GMO mobilization in Europe, impose environmental and administrative constraints on farmers which may limit the crop's distribution.

On the other hand, there where GMO are authorized and regulations are not very restrictive, they spread out on a grand scale. In fact, farmers find a real interest in using them. Without the moratorium France adopted in 2008, corn growers, mainly in the Southwest, would have gladly continued their launch: The 500 hectares cultivated in the Hexagon in 2005 rose to 22,000 in 2007. However, in terms of yield per hectare, the studies emphasize the marginal contribution of GMO technology. In the case of corn, average yields in the United States grew 28 percent between 1991-1995 and 2004-2008, but only 3 to 4 percent of that gain is imputable to transgenic corn seeds, indicate Union of Concerned Scientists researchers (3), with most of the increase attributable to other factors (progress in classic varietal selection, crop management techniques ...). The comparative advantage of GMO is elsewhere: the simplification of the farmer's work and the reduction in production costs. In 99 percent of cases, a GMO plant presents one, the other, or both of these two characteristics: tolerance for glyphosate, a large-spectrum herbicide, or insect repellent power due to the incorporation of Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt), a bacterial insecticide, gene. Tolerance for glyphosate allows applications over a longer period of the plant's growth as well as permitting use of only that herbicide. Another advantage: that avoids the need for mechanical weeding. As for Bt crops, they offer better resistance to insect attacks and generate savings on insecticides. In Spain, in the Aragon region, the final net gain, taking into account the extra cost of GMO seeds compared to conventional varieties, came to close to 120 Euros per hectare of corn ... but tended towards zero in other regions where insect attacks were more moderate (4).

The Transgenic Planet (in 2008)

All that would be almost good, if these GMO that are the joy of seed firms were not the last avatar of a chemical and industrial agriculture that has become unsustainable. An energy-devouring agriculture unfit for feeding the planet tomorrow, especially if global meat consumption - which requires vast agricultural spaces - were to continue indefinitely. And an agriculture with serious environmental impact. "We make the same mistakes and end up with the same problems," summarizes, INRA's Jacques Gasquez. This researcher emphasizes the development of weeds now resistant to glyphosate - today a dozen species - linked to usage of that herbicide. The same problems occur with the insecticide plants where we are beginning to see harmful insects that have become impervious - so requiring new applications. These problems of resistance to toxic substances have developed with the excessive use of chemistry in agriculture and are not unique to GMO. However, GMO support a phenomenon to which one continues to respond by hurtling full speed ahead. The seed companies, the INRA researcher explains, put the final touches today on varieties tolerant of a second herbicide, which one may add to glyphosate to master the rebellious weeds that will in their turn develop new resistances. That will eventually have to be vanquished with ever-stronger doses of chemicals ...

Uncomfortable Industrial Secret

To this problem, which is taking on a worrying turn, are added many uncertainties, whether concerning the effects of GMO contamination on wild and cultivated species or even possible toxic impacts on people that are difficult to detect when the authorizations for human and animal consumption are based on tests on laboratory rats limited to ... three months duration.

It's the same for GMO as for any new technology: certitude does not exist. Yet, a democratic choice has to be based on a better risk evaluation. But that clashes with industrial secrecy. "The technical files and information supplied by the seed firms to the administrations and their scientific committees for authorization have not been made public," rages researcher Gilles-Eric Séralini, Director of Criigen's scientific council (5). Which prohibits second opinions. On February 10, 2009, American universities - favorable to GMO - registered a complaint with the American Environmental Protection Agency since the seed companies de facto interdicted their work by refusing them access to certain data or by purely and simply withdrawing authorization to study GMO plants on their own. A right that the firms in an oligopolistic position assert in all legality; the seven of them, beginning with Monsanto, DuPont (Pioneer) and Syngenta, that control 62 percent of the market, can do so because their products are patented and so protected for 20 years. But their power goes much further: Dominant from their powerful research resources, these giant companies are multiplying their patents on the genetic constructions they elaborate from nature's resources and that could serve to manufacture the possible GMOs of the future, such as drought-resistant grains. Not only do these firms anticipatively confiscate the potential profits, but they also block the ability of public or independent expertise to illuminate these necessarily political choices.

Getting Our Bearings: Citizens Don't Really Have a Choice

The European directive of 2001 imposes labeling on food products that contain GMO, a victory for citizen mobilization in Europe. Unless one eats organic only (and pays the prices it commands) this labeling legislation - unique in all the world - nonetheless does not allow the consumer the free choice of eliminating GMO from his food. In fact, animal products (meat, milk, eggs, cheese) that are fed GMO soy escape that regulation: They are not transgenic. Yet, that's precisely the main issue: The GMO that Europe massively imports (and produces only very marginally) are almost exclusively intended for animal consumption. Will the situation evolve? This past April 3 in France, the National Consumer Council pronounced in favor of a "Fed without GMO" labeling for meat and milk, which has already appeared in Germany. Serious battles with the Americans of both North and South may be expected if such regulations come to fruition.

Notes

(1) Environics International, cited in "How have opinions about GMOs changed over time? The situation in the EU and the USA", Sylvie Bonny, November 2008.

(2) With the anecdotal exception of two varieties of carnations.

(3) Failure to Yield. Evaluating the Performance of Genetically Engineered Crops, UCS, 2009.

(4)http://ipts.jrc.ec.europa.eu/publications/pub.cfm?id=1580

(5) Committee for Independent Research and Information on Genetic Engineering (www.criigen.org).

--------

Translation: Truthout French Language Editor Leslie Thatcher.

Study Released in Argentina Puts Glyphosate Under Fire

Tuesday 28 July 2009

by: Marie Trigona | Visit article original @ Znet | AmericasIRC

Argentina has seen an explosion in genetically modified (GM) soy bean production with soy exports topping $16.5 billion in 2008. The fertile South American nation is now the world's third largest producer of soy, trailing behind the United States and Brazil. However, this lucrative industrial form of farming has come under fire with environmental groups, local residents, and traditional farmers reporting that GM soy threatens biodiversity, the nation's ability to feed itself, and health in rural communities. A study released by Dr. Andres Carrasco earlier this year reports that glyphosate causes birth defects.

Criticism of the soy farming model intensified recently when research released by Argentina's top medical school showed that a leading chemical used in soy farming may be harmful to human health. The study has alarmed policymakers in the South American nation.

A study released by an Argentine scientist earlier this year reports that glyphosate, patented by Monsanto under the name "Round Up," causes birth defects when applied in doses much lower than what is commonly used in soy fields.

The study was directed by a leading embryologist, Dr. Andres Carrasco, a professor and researcher at the University of Buenos Aires. In his office in the nation's top medical school, Dr. Carrasco shows me the results of the study, pulling out photos of birth defects in the embryos of frog amphibians exposed to glyphosate. The frog embryos grown in petri dishes in the photos looked like something from a futuristic horror film, creatures with visible defects - one eye the size of the head, spinal cord deformations, and kidneys that are not fully developed.

"We injected the amphibian embryo cells with glyphosate diluted to a concentration 1,500 times than what is used commercially and we allowed the amphibians to grow in strictly controlled conditions." Dr. Carrasco reports that the embryos survived from a fertilized egg state until the tadpole stage, but developed obvious defects which would compromise their ability to live in their normal habitats.

Pointing to the color photos spread on his desk, Dr. Carrasco says, "On the side where the contaminated cell was injected you can see defects in the eye and defects in the cartilage."

For the past 15 months, Dr. Carrasco's research team documented embryos' reactions to glyphosate. Embryological study is based on the premise that all vertebrate animals share a common design during the development stages. This accepted scientific premise means that the study indicates human embryonic cells exposed to glyphosate, even in low doses, would also suffer from defects.

"When a field is fumigated by an airplane, it's difficult to measure how much glysophate remains in the body," says Dr. Carrasco. "When you inject the embryonic cell with glysophate, you know exactly how much glysophate you are putting into the cell and you have a strict control."

Glyphosate is the top selling herbicide in the world and is widely used on soy crops in Argentina.

Monoculture soy is grown on more than 42 million acres of fields across Argentina and sprayed with more than 44 million gallons of glyphosate annually. It is part of a technological package sold by Monsanto that includes Round Up Ready seeds GM to tolerate the herbicide glyphosate. This allows growers to fumigate directly onto the GM soy seed, killing nearby weeds without killing the crop. In the winter, crops are sprayed to kill off weeds and seeds are then planted without having to plow the soil, a process commonly referred to as "no-till farming." Nearly, 95 percent of the 47 million tons of soy grown in Argentina in 2007 was genetically modified, adopting the Round Up ready technology marketed by Monsanto.

The study on the top-selling agrochemical has alarmed policymakers, so much so that Dr. Carrasco has received anonymous threats and industry leaders demanded access to his laboratory immediately following the study's release. Industry leader Monsanto wouldn't talk to the Americas Program for this story, but in a press release on its web site, the company says that "glyphosate is safe."

Many in the agro-business sector claim that Dr. Carrasco's study has little scientific basis. Guillermo Cal is the executive director of CASAFE - Argentina's association of agrochemical companies that counts Monsanto, Dow Agro-sciences, Dupont, and Bayer CropScience among its members. Cal dismissed the recent study conducted at the University of Buenos Aires. In an exclusive interview with the Americas Program, Cal rebuked Dr. Carrasco's study, stating, "There are hundreds of articles about the impact of glyphosate in amphibians and none of these articles have shown the disastrous effects that Dr. Carrasco is mentioning. I have the suspicion that these are headlines and probably [this study is a] politically motivated article."

On further investigation, it turned out that the studies that Guillermo Cal cited in the interview were all financed and conducted by the companies that market glyphosate. When asked about that, Cal replied, "The developing companies are the ones that have to finance these studies because we need to have proof of the innocuous character of the product before the product is launched."

Frog embryos injected with glyphosate developed obvious defects which would compromise their ability to live in their normal habitats.

Since Argentina's soybean boom in the late 90s, clinical studies have been conducted in communities reporting suspiciously high rates of cancer, birth defects, and neonatal mortality. However, industry leaders also refute these clinical studies, saying they are anecdotal and have little scientific basis. Among a corporate controlled scientific community it is notoriously difficult for clinical studies to "prove" the link between environmental contamination and health results, since life is not a "controlled environment."

In a small town bordering soy farms in the province of Cordoba, the Mothers of Ituzaingo group was formed in response to sudden increases in the local cancer rate. Ituzaingo has 5,000 residents - in 2001 they reported more than 200 cases of cancer and by 2009 that number has jumped to 300. This is 41 times the national average. (I conducted this calculation: the national average or percentage is 0.145 of the population diagnosed with cancer - in this town 6 percent of the population has cancer.) They have fought for regulations against fumigating soy crops in residential areas and a ban of agrochemicals.

Sofia Gatica is an activist with the Mothers of Ituzaingo. Sofia joined the grassroots group after suffering the death of her newborn baby. Her daughter was still born with a malformed kidney. Her 14-year-old daughter is currently undergoing treatment for toxicity in the blood. The toxin was identified as endosulfan, an insecticide used on soy fields.

Gatica describes the many birth defects that have occurred locally. "We have had children born with only two thumbs and no fingers, malformed kidneys, children with six fingers. We have had babies born without an anus, or with malformations in the intestines."

After years of documenting the tragedies, the Mothers of Itzuaingo decided to take their case to the courts. In 2006, they won their lawsuit in the provincial Supreme Court. Based on their findings, the court ruled to prohibit the use of agrochemicals within 1,000 meters of residential areas. The decision applies to the province of Cordoba while in the rest of the country farmers can continue to fumigate with no regulations.

The case of Ituzaingo is not an isolated case. For nearly a decade, communities have reported health problems from aerial and terrestrial fumigation with the arsenal of pesticides and herbicides used in industrial soy farming. And for nearly a decade they have been ignored. "Communities are literally fumigated with planes or with the terrestrial 'mosquito repellent' fumigations (similar to the DEET trucks used to fumigate U.S. neighborhoods in the 50s). Cases of health problems, miscarriages, birth defects, and cancer rates have multiplied at an alarming rate in communities surrounding the soy fields," says Carlos A. Vicente, head of information for Latin America at GRAIN.

The Campesino Movement of Santiago del Estero (MOCASE), a grassroots movement made up of traditional farmers and indigenous groups, has taken more than 100 accusations of agrochemical poisoning to court in Santiago del Estero. The only other case of a judge ruling against the use of herbicides occurred in the northern province of Formosa. The judge, Silvia Amanda Sevilla, was subsequently fired. No other judge in the country has ruled in favor of prohibiting fumigation using glyphosate or other herbicides and pesticides. The courts have either thrown out or ruled against every single claim brought by the plaintiffs. Dar√≠o Aranda, a journalist with the national daily, Página/12, has reported on numerous communities in soy-producing regions throughout the country that have faced severe health problems, including residents in the provinces of Buenos Aires, Entre Rios, Chaco, Santa Fe and Formosa.

Worse yet, research shows that the mostly rural communities that suffer the negative health effects of fumigations have not benefited from the soy explosion. On the contrary, in most regions families have been pushed off land taken over by soy farming, leading to a loss of livelihood in addition to the severe health risks. According to a 2002 agricultural census, in four years more than 200,000 families were driven from their traditional farms, and most of the families relocated in working class belts outside of major cities.

Authorities and industry representatives maintain that the clinical studies and citizen complaints must be backed up by "serious studies" in order for them to act. Gatica says that GM seed and agrochemical companies have converted Argentina into an experimenting ground to test the toxicity of their herbicides and pesticides, principally glyphosate and endosulfan. "We can prove that agrochemicals have harmed us. We can prove this with studies and with whatever is left of our children," says Gatica. The anger in her voice reflects the grief and rage she has channeled into this David and Goliath battle.

The expansion of soy means the increased use and concentration of glyphosate. Over time, Round Up herbicide loses its technological battle with evolution and new weeds develop that are more resistant to the herbicide, explains Javier Souza Casadinho, professor at the University of Buenos Aires and regional coordinator of the Latin American Action Network for Alternative Pesticides. "Producers must use more applications, and in higher doses with higher toxicity‚ the application has gone from three liters in 1999 to the current dose of 12 liters, per hectare," says Souza.

GM soy was swiftly approved for cultivation in Argentina in 1996, under former Agricultural Secretary Felipe Sola. A 180-page file report, prepared by GM giant Monsanto in English without a Spanish translation was the only document evaluated before Sola approved GM soy after only 81 days of review. The former secretary and investor in the soy industry won a seat in the legislature in the June 2009 elections, riding in on his opposition to President Cristina Kirchner's decision to increase the export tax on soy. Argentina's current Secretary of Agriculture Carlos Cheppi refused the Americas Program's formal request for an interview. His press secretary said Ricardo Gouna is "unwilling to talk about the use and regulation of agrochemicals in Argentina's soy industry."

The study in Argentina is not the only research concluding that the number one selling herbicide may be harmful to human health. Gilles-Eric Seralini, professor at the University of Caen and specialist in molecular biology, led a study that concluded the herbicides in the Round Up Ready package causes cells to die in human embryos.

"Even in doses diluted a thousand times, the herbicide could cause malformations, miscarriages, hormonal problems, reproductive problems, and different types of cancers," said Dr. Seralini in an interview with Dario Aranda published in Página/12. Round Up Ready is currently marketed in more than 120 nations. Latin American nations Brazil, Uruguay, and Paraguay are the region's fastest-growing markets.

Since Carrasco's study was released in April, the NGO Association of Environmental Lawyers (Aadeaa) petitioned the Supreme Court to ban the use of glyphosate and endosulfan. Policymakers are currently considering the petition. The National Committee on Ethical Science has also recommended that the Agricultural Ministry create an investigative committee to urgently evaluate the effects of the number one selling herbicide in Argentina. Dr. Carrasco says that his study and previous studies should serve as a red-light warning for policymakers charged with evaluating regulations for glyphosate. The herbicide is currently categorized as a level 4 toxin - the lowest level possible for agrochemicals. In science and medicine, when you suspect that something dangerous is occurring, you need to implement the precautionary principle, which dictates: "I need to take precautions; I can't ignore the problem; I can't wait until there are a lot of deaths to intervene." Unfortunately, Argentine courts and federal, state, and local governments appear not to agree. Given the enormous economic stakes, precaution may come too late as soy has invaded the majority of Argentina's highly fertile land leading to irreversible social, health, and environmental consequences.

--------

Marie Trigona is a journalist based in Argentina and writes regularly for the Americas Program (www.americaspolicy.org). She can be reached at mtrigona@msn.com.