Egg rationing in America has officially begun

Roberto A. Ferdman

In recent days, an ominous sign has appeared throughout Texas. "Eggs [are] not for commercial sale," read warnings, printed on traditional 8 1/2-by-11-inch pieces of white paper and posted at H-E-B grocery stores across Texas. "The purchase of eggs is limited to 3 cartons of eggs per customer."

H-E-B, which operates some 350 supermarkets, is one of the largest chains not only in the state, but in the whole country. And it has begun, as the casual but foreboding notices warn, to ration its eggs.

"The United States is facing a temporary disruption in the supply of eggs due to the Avian Flu," a statement released on Thursday said. "H-E-B is committed to ensuring Texas families and households have access to eggs. The signs placed on our shelves last week are to deter commercial users from buying eggs in bulk."

The news, as the grocer suggests, comes on the heels of what has been a devastating several months for egg farmers in the United States. Avian flu, which has proven lethal in other parts of the world, has spread throughout the United States like wildfire. Since April, when cases began spreading by the thousands each week, the virus has escalated to a point of national crisis.

As of this month, some 46 million chickens and turkeys have been affected, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Nearly 80 percent of those are egg-laying hens, a reality that has been crippling for the egg industry.

But it's becoming increasingly clear that it isn't merely those who produce eggs that will suffer. Those who eat them will pay a price, too.

The wholesale price of eggs sold in liquid form (a.k.a. egg beaters, the kind used by large food manufacturers) has skyrocketed — from $0.63 per dozen to more than $1.50 — since the virus began to spread. While that stands to affect the price of breads, pastas, cakes and other commercial confections made with eggs, it also bodes poorly for food service providers, such as McDonald's, which sell millions of egg-filled meals every morning. Texas-based fast-food chain Whataburger recently announced that it will be shortening its breakfast hours for the foreseeable future.

"We know this is no fun for anyone and hope this doesn’t last long, and we apologize the supply of eggs cannot currently meet demand," the company wrote on its Facebook page.

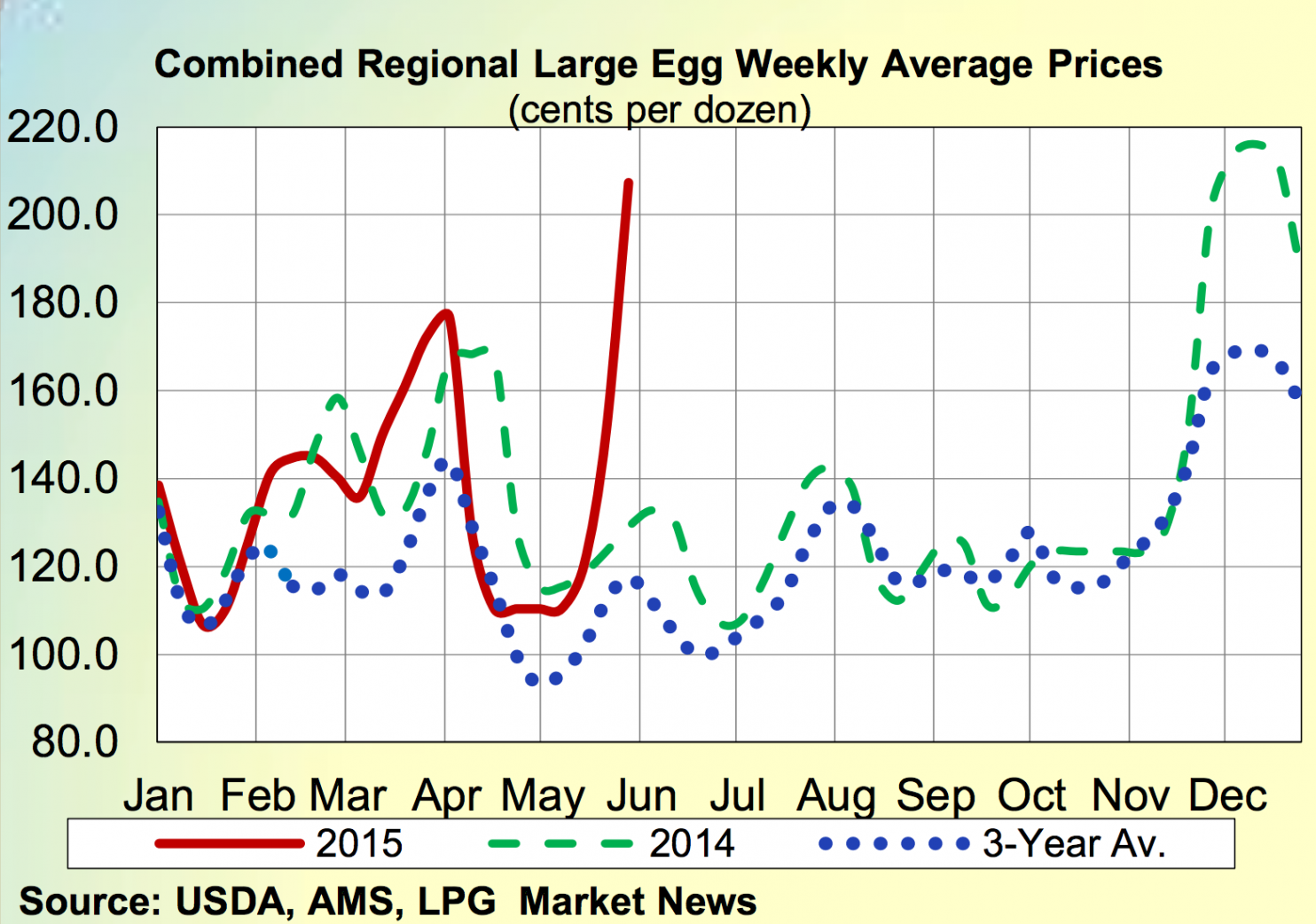

In-shell egg prices have risen too. The average price per dozen has just about doubled since the end of May, according to the USDA. Have a look at that red line in chart below.

But incremental price increases are hardly as noticeable as strict limits on purchases, such as those already appearing at one of the country's largest supermarket chains, which makes the signs at H-E-B stores all the more foreboding. H-E-B has called the disruption "temporary" but hasn't delineated any time frame for the three-dozen-egg limit.

Given how fruitless efforts have been to contain the flu so far, it's hard to imagine the system will be flooded with a fresh stream of eggs any time soon. It seems likely, in other words, that other grocers will begin rationing eggs, too, before H-E-B is able to sell patrons as many as they wish to eat.

And with each wrinkle of bad news, the idea of a national egg shortage, which was once uttered as though it were a mere apocalyptic musing, is suddenly looking like a real possibility.

Roberto A. Ferdman is a reporter for Wonkblog covering food, economics, immigration and other things. He was previously a staff writer at Quartz.

SEE VIDEO