Karl Rove: He's Back, Big Time [To get rid of Obama]

Paul LM Barrett, Business Week

Karl Rove. (photo: UPI)

n the evening of June 29, Amedeo Scognamiglio, a jewelry designer on the Isle of Capri, met friends for drinks at the elegant Grand Hotel Quisisana. Around midnight, Scognamiglio says, “I noticed some familiar American faces.” He took to Twitter. “What,” he wanted to know, “is Karl Rove doing at the Quisisana with Steve Wynn?!” The answer came zinging right back from @KarlRove: “Part of a group enjoying really good Bellinis on a beautiful Capri night!”

n the evening of June 29, Amedeo Scognamiglio, a jewelry designer on the Isle of Capri, met friends for drinks at the elegant Grand Hotel Quisisana. Around midnight, Scognamiglio says, “I noticed some familiar American faces.” He took to Twitter. “What,” he wanted to know, “is Karl Rove doing at the Quisisana with Steve Wynn?!” The answer came zinging right back from @KarlRove: “Part of a group enjoying really good Bellinis on a beautiful Capri night!”

Rove is a tech-geek. On Sept. 11, 2001, he was the only White House staff member connected to BlackBerry e-mail on Air Force One as the plane ferried President George W. Bush back and forth across a panicked nation. When he made his Bellini tweet, Rove was on the Amalfi Coast honeymooning with his third wife, Karen Johnson, a Republican lobbyist. On Twitter, Rove did not refer by name to Wynn, though the two men are friends. Earlier in June, the casino mogul joined a select group of guests at the Rove-Johnson nuptials in Austin. All of this, be assured, has more than gossip-page significance: Wynn is just one of many mega-wealthy backers whose enthusiasm and checkbooks have fueled a Karl Rove Renaissance that’s redefining the business of political finance.

The bespectacled 61-year-old, once known as Bush’s Brain, left the White House five years ago. His patron was sinking in the polls, and Rove himself had barely escaped criminal indictment. Now he’s back—big time, as his friend former Vice President Dick Cheney might say. In a performance that rivals Rove’s nurturing of a famously inarticulate Texas governor into a two-term president, the strategist is reengineering the practice of partisan money management in hopes of drumming Barack Obama out of the White House.

Consider the case of Wynn. Variable in his political allegiances, the gambling magnate has said publicly that he voted for Obama in 2008, only to change his mind over what he came to perceive as the president’s regulatory hubris. In swooped Rove. As first reported by Politico, he persuaded Wynn that the best way to oust Obama was to contribute millions of dollars to a Washington-based group Rove co-founded in 2010 called Crossroads GPS. Wynn’s preference for anonymity in such transactions posed no obstacle. That’s the whole idea behind Crossroads GPS. Although its initials stand for “Grassroots Policy Strategies,” the organization was set up to receive unlimited, undisclosed contributions from industrialists, financiers, and other loaded insiders such as Wynn. (“We do not comment on specific donations,” says a Wynn spokesman.)

In the strange realm of campaign finance, the Internal Revenue Service classifies Crossroads GPS as a nonprofit, nonpolitical “social welfare” organization—a 501(c)(4) in tax code parlance—that does not have to identify its backers. Crossroads GPS channels money into “issue” advertisements, which implicitly, but not very subtly, attack Obama and other Democrats. Perhaps you’ve seen one on cable television: “It wasn’t supposed to be this way,” a mournful-sounding female narrator intoned in one weeklong, $8 million campaign GPS ran in mid-July in Florida, Michigan, Ohio, and six other hotly contested states. “Over three years with crushing unemployment; American manufacturing shrinking again,” the ad continued. “President Obama’s plan: spend more. He’s added over $4 billion in debt every day. The economy is slowing, but our debt keeps growing.”

To maintain its supporters’ anonymity, a social welfare group like GPS must not have a “primary purpose” of a political nature, and it cannot coordinate strategy with candidates. In an election season, however, only a very naïve or obtuse viewer would miss the point of the organization’s prolific ads.

For conservative donors willing to reveal themselves, Rove designed a sister group, a “super PAC” called American Crossroads, which operates from the same offices as GPS, with some of the same executives, employees, copywriters, and consultants. It, too, is technically independent from the Romney campaign. Known as a 527, it does report its donors to the Federal Election Commission, and it can indulge less coyly in pushing Romney and other Republicans. On July 19 the Crossroads super PAC began a separate nine-state $9.3 million ad blitz defending Romney from Democratic charges that he helped move American jobs overseas during his tenure as chief executive of the private equity firm Bain Capital. Of Obama, the ads assert: “The press, and even Democrats, say his attacks on Mitt Romney’s business record are … ‘misleading, unfair, and untrue.’”

Democrats, for their part, are doing the same sort of thing, with their own 527s and 501(c)(4)s. The supposedly unaffiliated Democratic super PAC buying ads for Obama is called Priorities USA Action. Back in the 2000s, Rove says in an e-mail interview, it was Democratic-leaning labor unions and liberal plutocrats such as hedge fund financier George Soros and insurance tycoon Peter Lewis who provoked the unlimited-outside-money boom. Whoever started the gonzo fundraising wars—and in 2010, the Supreme Court played an important, if misunderstood enabling role with Citizens United v. FEC—the Crossroads operation is way out in front this election cycle. Along with the billionaire Koch brothers, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, and other conservative allies, the Crossroads-led offensive is collectively poised to spend more than $1 billion on the 2012 elections, according to Republican operatives. That’s roughly twice—repeat: twice—what Democrats expect to spend by means of their super PACs and social welfare groups.

“What we have,” says Brendan Doherty, a political scientist at the U.S. Naval Academy and author of new book The Rise of the President’s Permanent Campaign, “is an irrational, incoherent, out-of-control campaign finance apparatus” that shifts influence from traditional parties to wealthy secret donors and corporations.

Not to worry, Rove reassures. He says his goal is to solidify Republican control in Washington, not subvert the party system. But he’s adjusted to changing circumstances. “I like stronger parties, rather than weaker parties,” he explains, “but the campaign finance reforms of the last 40 years have tended to weaken parties and strengthen outside groups. … I’m focused on operating within the system we have.”

In the summer of 2007, Rove limped away from the Bush White House substantially depleted. The previous year he’d appeared no fewer than five times before a federal grand jury investigating official leaks to the media about Valerie Plame’s identity as an undercover operative for the Central Intelligence Agency. Plame’s husband, a former U.S. ambassador, incurred White House wrath by publicly questioning the invasion of Iraq in 2003. Although Rove denied outing Plame, he acknowledged in his 2010 memoir, Courage and Consequence: My Life As a Conservative in the Fight, that he came whisker-close to facing criminal charges. The controversy “had exhausted more than my physical reserves,” he wrote. “It had also burned through a significant portion of my family’s finances.”

Almost immediately, Rove drafted his next chapter. He engaged attorney Bob Barnett, the go-to Washington literary representative, to sell his memoir. The spirited 608-page work settled scores aplenty and became a New York Times bestseller. Continuing to repair his personal brand, Rove signed on with Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp. (NWS) to write a column for the Wall Street Journal editorial page and comment frequently on Fox News. His reinvention as a media wise man betrayed more than a whiff of chutzpah. The election victories for which Bush called Rove “the architect” led, after all, to quagmires in Iraq and Afghanistan. At home, the Bush team left behind failed reform initiatives on Social Security and immigration, record deficits, and the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression. Still, whatever the outcome of his patron’s governance, Rove has few rivals in his mastery of campaign mechanics. Rather than using the Journal and Fox gigs to coast, he’s offered data-rich, partisan-spiced procedural analysis, and built up a substantive personal website. (An historian by avocation, he’s posted reviews of the last 60 books he’s read.)

Perched safely on the sidelines, he also dodged the Republican disaster in November 2008. At the center of that debacle, presidential candidate Senator John McCain (R-Ariz.) distanced himself from outside political action committees and accepted public financing, a decision that had the effect of limiting what he could spend in his race against Obama. The Democrat turned down public money, revealed himself to be a fundraising dervish, and outspent his opponent by nearly two-to-one. Rove watched carefully. “After seeing their success and recognizing liberal groups and unions would systematically spend hundreds of millions of dollars every cycle,” he says, some on the right “decided to create an enduring entity as a counterbalance.” Those entities are the Crossroads groups.

Rove’s return to the arena coincided with a major campaign-finance ruling by the Supreme Court. It irritates Rove that Obama has succeeded in crafting the conventional wisdom on Citizens United. According to Obama’s account, a 5-4 conservative judicial pronouncement liberated a cabal of zillionaires and corporations to launch a hostile takeover of American politics. In his State of the Union Address in January 2010, the president blamed the justices, some of whom were seated before him, for empowering “America’s most powerful interests, or worse … foreign entities” to “bankroll” elections. Television cameras caught Justice Samuel Alito mouthing the words, “Not true.”

Rove agrees with Alito. Obama’s bit about “foreign entities” giving to campaigns was flat wrong; that remains illegal. Citizens United did clarify that corporations have a First Amendment right to political speech in the form of spending for advocacy. The majority tossed out an important 1990 precedent and invalidated certain legislative restrictions on how and when companies and unions can deploy political dollars. Spending has increased dramatically in the wake of Citizens United, much to the advantage of Republicans, and yet the notion that the ruling sparked a brand new conservative bonanza is misleading. “The left,” Rove notes, “pioneered the use of 527s and 501(c)(4)s years ago, spending millions of dollars to influence public opinion and the policy landscape, on issues spanning the environment to the Iraq War. Drawing on their example, Crossroads was being planned before Citizens United, and would exist with or without Citizens United.”

A quick look at campaign-finance history illustrates what he means. Secret contributions and sundry other corrupt actions culminating in the Watergate scandal led to reform legislation in the mid-1970s. Before the ink had dried on the new rules, the Supreme Court intervened in 1976, in Buckley v. Valeo, to remind lawmakers that the First Amendment complicates any inclination to limit political expression. The upshot was a problematic system that curbed contributions to candidates in the interest of reducing quid pro quo corruption, but encouraged open-ended expenditures in the name of free speech. Cue the K Street loophole artists.

By the 1990s labor unions and companies had perfected the “soft money” gambit, funneling hundreds of millions of dollars to political parties, rather than particular candidates. The Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002, known as McCain-Feingold, was supposed to wall off soft money. In doing so, the law inadvertently redirected the cash flow to 527s, such as Swift Boat Veterans for Truth, to which conservatives could give unlimited amounts to assail the war record of Senator John Kerry (D-Mass.). Another alternative was the 501(c)(4) social-welfare group devoted to issue advocacy, which did not require the disclosure of donors’ names. Six years before Citizens United, the basic technology for an outside-spending arms race was in place.

In 2004 a 527 called America Coming Together led a $200 million initiative, partly financed by Soros and Lewis, to unseat George W. Bush. One reason many forget this liberal financial surge is that it failed; Kerry, a diffident campaigner, lost by 34 electoral votes. Republicans, for their part, didn’t fully appreciate the advent of outside groups because they were lulled by Bush’s talent for gathering direct-contribution checks with the assistance of “bundlers,” the dedicated supporters and lobbyists who aggregate individual donations.

Rove and his consultant friend Ed Gillespie—now a paid senior adviser to the Romney campaign—had warned from the inception of McCain-Feingold that it would lead to problems for Republicans. Borrowing from the chorus of the classic Sonny Curtis song, Gillespie joked that as RNC chair for the 2004 election cycle, he “fought the law, but the law won.” In 2009, Rove and Gillespie decided it was time for Republicans to stop whining and turn the tables.

As they began planning how to make Obama a one-term president, Rove and Gillespie saw most Republican outside organizations as either one-shot affairs, like the Swift Boaters, or preachers to the base that pushed candidates to the extreme right. The anti-tax Club for Growth fit in the latter category. Some wealthy political benefactors had their own groups, Rove notes, most of which were run by a single strategist who siphoned off enormous fees for as long as the sponsor would tolerate it.

Rove pitched his proposed startup as a more professional alternative, one built to have impact in 2010 but endure long beyond. “The business model of a consultant-driven, vendor-directed entity that hired itself increasingly lacked credibility with donors and was unsustainable,” Rove explains. Among those who were convinced and made big contributions: Richard Baxter Gilliam, a Virginia coal mogul; Houston homebuilder Bob Perry; and Harold Clark Simmons, a Dallas industrialist.

A vacuum at the once-mighty RNC made Rove’s work easier, and more urgent. At RNC headquarters, Michael Steele, the chairman for the 2009-10 cycle, was singularly ineffective as a fundraiser and prone to mishaps, such as getting into public scraps with the radio host Rush Limbaugh and suggesting that Republicans needed a “hip hop” overhaul.

To guide Crossroads, Rove convened a board of directors of conservative notables—Chairman Mike Duncan of Kentucky had served as chairman and treasurer of the RNC; Director Jo Ann Davidson of Ohio had also led the RNC and oversaw the 2008 Republican convention—a signal that it would be beholden to no single candidate or contributor. The board hired as chief executive officer Steven Law, an affable attorney and campaign veteran who had worked on Capitol Hill for Senator Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) and for President Bush in the Department of Labor. As general counsel of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce in 2007-08, Law spearheaded a successful drive to kill the proposed Employee Free Choice Act, a pro-union measure. The locus of the party’s financial strategizing shifted to Rove’s living room on Weaver Terrace in Northwest Washington.

During sessions of the “Weaver Terrace Group,” representatives of the embryonic Crossroads organization gathered with counterparts from groups such as the Chamber of Commerce, Americans for Tax Reform, and Americans for Prosperity, the funding vehicle affiliated with the billionaires David and Charles Koch. Crossroads served as referee, says CEO Law. “Conservative activists tend to act like six-year-olds on soccer teams,” he explains, “with everyone grouping around the ball and getting in each other’s way. Karl’s idea was that all of these organizations should share information, coordinate polling, reduce redundancy.”

Together with a follow-on ruling by the federal appeals court in Washington, Citizens United knocked several crucial holes in McCain-Feingold. Corporate and union money, for example, could now be used without restriction for “electioneering communications,” meaning radio and TV ads that mention a candidate’s name within 30 days of a primary or 60 days of a general election. More important than the incremental increase in campaign-law porosity, though, was the passionately phrased celebration by Justice Anthony Kennedy of political spending in its manifold forms. Kennedy’s majority opinion declared that “the appearance of influence or access … will not cause the electorate to lose faith in our democracy.” Kennedy continued: “The fact that a corporation, or any other speaker, is willing to spend money to try to persuade voters presupposes that the people have the ultimate influence over elected officials.” In Kennedy’s syllogism, democracy benefits from more speech. Political money is speech. Therefore democracy benefits from more political money.

The Citizens United decision all but erased any lingering taint from writing large campaign checks. “The decision is simply brilliant,” says the white-collar defense attorney John Dowd, a partner in Washington with the politically active law firm Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld. “I’m a big believer in the First Amendment and more speech by everyone, not just the liberal elite.” Dowd, whose most recent high-profile client was the (convicted) Galleon Group hedge fund manager Raj Rajaratnam, has been a steady Crossroads contributor in $10,000 increments. “I see Karl from time to time, and he’s a very gifted analyst who does his homework,” says the lawyer. “His people have a capability I don’t have as a citizen to decide how to get the word out.”

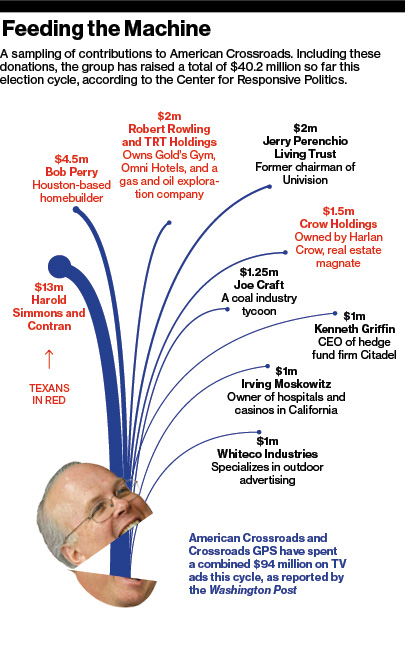

Corbis; Data: Center for Responsible Politics

The word that Dowd and many other Rove contributors want amplified is not the tear-the-walls-down Tea Party howl. If there is an establishment Republican alternative to the Tea Partiers, it is embodied by Rove. In October 2010 he used an interview by the Telegraph in London to question Sarah Palin’s suitability for the White House. He helped marginalize Christine O’Donnell, the right-wing senatorial aspirant from Delaware with a colorful financial history and a past interest in witchcraft. O’Donnell, Rove told Fox viewers, “does not evince the characteristics of rectitude and truthfulness and sincerity and character that the voters are looking for.” She lost in November 2010 to Democrat Chris Coons.

In their rookie election cycle, the pair of Crossroads groups aimed to raise $45 million. They ended up with $71 million. “Being the outsiders, trying to stop an incumbent is good for raising opposition money,” Law says, noting a basic tenet of attack-ad finance. For Democrats in 2010—and in 2012—it has been more of a challenge to ask for large checks to maintain the status quo.

Focusing primarily on Senate contests, while other conservative groups battled on the House side, the Crossroads groups tallied a 16-14 record in the 30 races they joined in 2010. Rove’s minions did not dislodge Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, despite spending $4.3 million on ads in his home state of Nevada. Crossroads executives argue that the most relevant measure of their impact in 2010 was that along with the other outside Republican groups, they stretched Democrats’ resources and sharpened the right’s attack on taxes and cap-and-trade climate legislation. Overall, Republicans won a tremendous midterm victory, retaking the House and gaining ground in the Senate.

Crossroads’ headquarters is a plain set of offices on the 12th floor of a blocky Washington building. The first thing greeting a visitor is a poster hijacked from a liberal protest. “Indicted: Karl Rove and American Crossroads and Crossroads GPS,” says the ersatz wanted notice. The mock charges include “conspiracy with billionaires to elect politicians who will do their bidding at the expense of the health and security of the 99 percent.”

The Crossroads groups are staffed leanly, with about 20 people, half of them junior researchers peering at laptops. Apart from his satirical mug shot, Rove is nowhere to be seen on this day. He holds no official position at Crossroads, draws no salary from the groups, and doesn’t get reimbursed for plane fare or lunches. He spends most of his desk time at Karl Rove & Co., a legally separate firm a few blocks away that oversees his media activities and well-paid public speaking. Rove, according to colleagues, devotes about a third of his working hours to Crossroads, almost all of it fundraising and private kibitzing with donors. At those skills, he has few rivals. “What Karl says goes,” says contributor John Dowd. “I trust him.”

Determining which institutional hat Rove is wearing at any given moment is not easy. Is he on Crossroads duty or personal business when he socializes with Steve Wynn in Capri? Rove talks to candidates, but the Crossroads groups by law aren’t permitted to “coordinate” with those candidates. Crossroads can’t endorse Romney, but it unabashedly defends him against Obama’s outsourcing assault.

When Romney hosted a gala retreat for individual contributors at a Utah resort in late June, Rove spoke on a panel and mingled as a featured guest. Presumably, he did not coordinate with the campaign, but how would you categorize what he did do? As noted, Crossroads co-founder Gillespie, who has his own consulting firm, is now working for Romney. Crossroads’ political director, Carl Forti, helped start and advises the Romney-devoted super PAC Restore Our Future. There is no shortage of cross-pollination. In Washington, only beleaguered good-government activists seem to take seriously the blurry demarcations of campaign finance law.

The FEC invites cynicism. Its six commissioners are divided 3-3 along partisan lines and, on meaningful issues, they seem unable to do anything other than reach stalemate. Although the terms of five of the six commissioners have expired, Obama gave up on nominating replacements after his first selection stalled in the Senate. With a tone that can only be described as half-hearted, the Obama campaign’s chief counsel, Robert Bauer, filed a complaint about Crossroads GPS with the do-nothing agency in June. In a personal letter he simultaneously sent to Rove and Law, Bauer said the filing “lay[s] out the case—obvious to all—that Crossroads is a political committee subject to federal reporting requirements.” Bauer went on to predict that the Rove camp will “fight this out” until after the election, at which point disclosure would be moot.

Crossroads denies the Bauer allegation, and Rove offers no apology. “It’s ironic,” he says, “that many of those who are squealing the loudest now [about Crossroads] are the same people who were mute when groups on the left were pioneering the use of 527s and 501(c)(4)s. … Liberals cheered then but are now quick to try and stop conservatives from using the techniques they used in the past.”

He and his acolytes are clearly enjoying themselves. This is something that Rove’s many psychoanalysts in the media and among Democrats seem to forget: He really loves the fight.

On the day in late February when Bob Kerrey, the former Nebraska senator, announced he would seek his old seat, American Crossroads decided to remind the politician that he’d been out of office for more than a decade, most recently serving as head of the New School, a liberal institution in the un-Nebraskan environs of New York. “A huge cooler of frozen Runzas was delivered to our house in Manhattan when Bob was in Omaha to declare his candidacy,” Kerrey’s wife, Sarah Paley, wrote in an article in the July issue of Vogue. Cabbage-and-beef Runza sandwiches “are to Omaha what Philly cheesesteaks are to Philadelphia or muffulettas are to New Orleans,” Paley explained. Rove’s group wanted “to reinforce the notion that Bob was a carpetbagger.”

On a more serious level, Rove has spent much of last year steering his own party away from fringe presidential candidates with no chance of getting elected. (Former pizza executive Herman Cain was “not … up to the task,” Rove told his Fox followers.) Once Romney shook off his primary competitors, Rove turned his energies to promoting the former Massachusetts governor, with whom he was not previously close. Unlike the 2010 midterms, when Rove and Crossroads concentrated on turning out diehard conservatives, 2012 is all about independents, according to Law, including those who voted for Obama in 2008 but now may feel disappointed by the faint economic recovery.

In his July 19 Wall Street Journal column, “Obama Gets Down and Dirty,” Rove warned of “the danger for Mr. Romney” posed by Obama’s attack about outsourcing and tax returns. “If these charges go unrefuted,” Rove wrote, “they could discourage swing voters from going for [Romney] this fall. … This is an opportunity to remind voters—in a tone of disappointment and regret, not anger and malice—that Mr. Obama’s negative attacks will not put anyone back to work, reduce our growing national debt, or get America moving in the right direction.” On the very same day, Crossroads took a tougher tone, rolling out its ad campaign calling Obama’s contentions “misleading, unfair, and untrue.” A clever one-two punch, delivered entirely independent, needless to say, of the Romney campaign.

http://readersupportednews.org/news-section2/318-66/12639-focus-karl-rove-hes-back-big-time?tmpl=component&print=1&page=